As mutações de David Cronenberg: um tributo a um dos maiores artistas do cinema

CRONENBERG’S MUTATIONS

Article by Eduardo Carli de Moraes

PROLOGUE

I have recently spent a whole afternoon wandering around at the Evolution exhibition, wonderfully produced by the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). It was such an amazing tribute to one of Canada’s greatest artists alive, David Cronenberg. I was already an admirer of his oeuvre – I’ve watched every film that Cronenberg has ever delivered, and some of them several times – but TIFF’s homage to this great creative mind took me on a thrilling “trip down memory lane” (to quote a memorable line by Ed Harris’ character in A History of Violence).

Since the late 1960s, Cronenberg has been producing some of the most tought-provoking and original films I’ve ever seen, and in this article I intend to argue that his body of work deserves our high praises for its artistic accomplishments. I don’t see why he should be confined within the limits of genres such as science fiction and horror: Cronenberg has gone way beyond the boundaries of “specialized filmmaking” and has built a cinematic legacy that bears the mark of far-sighted vision and unique imagination.

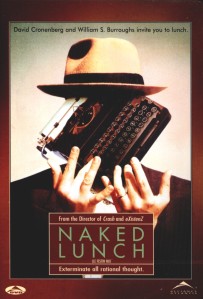

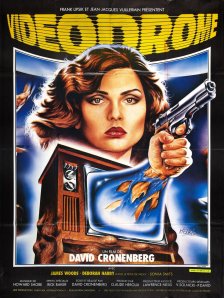

Here is an artist that never shies away from challenging themes: he has adapted to the big screen some works of literature deemed “unfilmable” (such as William Burrough’s Naked Lunch or Don De Lillo’s Cosmopolis); he has depicted sexual perversions and car-fetishism in impacful ways (in his film on J. G. Ballard’s Crash); he has engaged in a debate with Marshall McLuhan’s theories about media and its social effects (in Videodrome); he has explored the mysteries of schizophrenia, paranoia, depression, identity crisis, among other dark corners of the mind (in films such as Dead Ringers, The Brood, Spider…). Cronenberg, to sum things up, may be understood as a philosopher of cinema, who uses his art in order to understand the world around him, to share his fears and doubts about the paths treaded by Western civilization, and to awaken us from the slumbers of conformity by sounding the alarms on some doubtful process through which the human mind and body is being transformed and mutated.

Here is an artist that never shies away from challenging themes: he has adapted to the big screen some works of literature deemed “unfilmable” (such as William Burrough’s Naked Lunch or Don De Lillo’s Cosmopolis); he has depicted sexual perversions and car-fetishism in impacful ways (in his film on J. G. Ballard’s Crash); he has engaged in a debate with Marshall McLuhan’s theories about media and its social effects (in Videodrome); he has explored the mysteries of schizophrenia, paranoia, depression, identity crisis, among other dark corners of the mind (in films such as Dead Ringers, The Brood, Spider…). Cronenberg, to sum things up, may be understood as a philosopher of cinema, who uses his art in order to understand the world around him, to share his fears and doubts about the paths treaded by Western civilization, and to awaken us from the slumbers of conformity by sounding the alarms on some doubtful process through which the human mind and body is being transformed and mutated.

Some oversensitive people may certainly turn away from his work in disgust and horror, claiming that the guy is obsessed with disgusting creatures, nasty and monstruous mutants, scary uncontrolable viruses, and lots of bloodshed and carnage. There’s definetely a B-movie flavour to some of Cronenberg’s work, but this doesn’t mean his investigations are narrow and shallow. If some of his movies are far from being eye-candy, and if his esthetic choices have a strong tendency against kitsch, it leads us to ask: is the role of the artist to caress us and entertain us rather than to provoke us, shock us and kick us out of our comfort zones?

In the following explorations of Cronenberg’s films, I’ll attempt to throw the spotlight on the great contribution his art embodies as a reflection upon human psychology and the mysteries that underlie the mutations of our identities in the midst of our society’s ever faster techno-scientific transformations.

I. THE NEW FLESH

At TIFF’s Evolution exhibition, it was stated that “Cronenberg demonstrates a keen interest in doctors and scientists who initiate experiments with unforeseen, often disastrous, consequences”. Very well remarked: in Cronenberg’s realm, science and technology often produces “disasters” and “monsters”. Things never seem to turn out the way they had been planned to. There’s an abyss between good intentions and the actual outcomes of the experiments – and this abyss is one that Cronenberg’s loves to explore. In many cases, it’s as if Science is being seen from the lenses of its victims, from the perspective of the abused or the deranged by it.

At TIFF’s Evolution exhibition, it was stated that “Cronenberg demonstrates a keen interest in doctors and scientists who initiate experiments with unforeseen, often disastrous, consequences”. Very well remarked: in Cronenberg’s realm, science and technology often produces “disasters” and “monsters”. Things never seem to turn out the way they had been planned to. There’s an abyss between good intentions and the actual outcomes of the experiments – and this abyss is one that Cronenberg’s loves to explore. In many cases, it’s as if Science is being seen from the lenses of its victims, from the perspective of the abused or the deranged by it.

“History is a nightmare from which I’m trying to awake”, goes the famous saying by James Joyce in Ulysses. Watching David Cronenberg’s films I frequently get a feeling of entering a nightmarish world, where epidemics and plagues rage, and human heads suddenly explode, and brains get messed-up by medical interventions, consumption of pharmaceutical drugs, or misguided scientific manipulations.

It seems Science is a nightmare from which Cronenberg is trying to awake. And that by filming his dystopic visions he suceeds in sharing his nightmares with his perplexed audience. William Burroughs once said, later to be quoted by Kurt Cobain in a punkish Nirvana song: “just because you’re paranoid it doesn’t mean they’re not after you.” Likewise, it could be said of Cronenberg’s filmed nightmares: just because they’re pessimistic and terrifying, it doesn’t mean they can’t turn out to become reality. Just remember Chernobyl, in the past; just take a look at Fukushima, in the present; with these catastrophes in mind, Cronenberg’s phantasies will appear to our eyes as explorations of possibilities that we might unfortunely realize.

The originality of David Cronenberg cinema lies in, among other elements, the way he questions the consequences of technological “advancements” and scientific experiments: it can be a new brand of psychotherapy that relies on the un-repressed expression of rage (The Brood); it can be the evolution in video-games and artificial/digital environments (eXistenZ); it can be a new drug supposedly destined to turn life on Earth into a chemically induced Paradise (ephemerol in Shivers); it can be innovations in the fields of surgery, genetics or robotism…

Cronenberg’s cinema is surely dystopic, dismal, pessimistic, and one gets a “mood”, from his films, of anxiety and preocupation arising from the possible outcomes of our self-remaking, of mankind’s efforts to transform itself and to transcend its present limitations. Everyone who’s seen some of his films knows that scientific experiments – including the ones inside the field of Psychology, which interests Cronenberg very lively! – can end up going terribly wrong. And one of the thrills of watching his movies derives from the fact that we know this artist is not going to spare us, that he’s gonna make us confront some bloody and disruptive occurences.

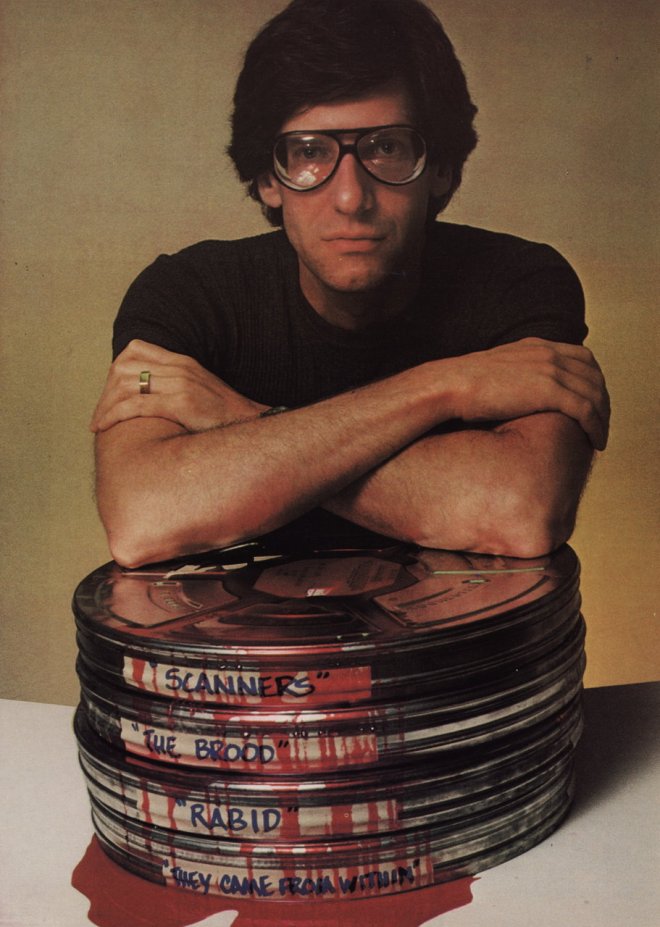

Since the beggining of his carreer, with Stereo (1969) or Crimes of The Future (1970), Cronenberg was into description of “laboratorial environments”, but within them there were no rat labs: in his films, the rat labs are always human beings. In one interview, the director states that he never makes “monsters movies”, but rather describes the ways through which the human body is transformed into a monstruous and uncontrolable post-human organism. In Cronenberg, the illusion of safety and control almost always ends up terribly shattered to pieces with the eruption of chaos and unpredicted consequences.

TIFF’s exhibittion EVOLUTION claimed that Cronenberg must be understood as one of the greatest thinkers in the whole of Canadian culture – and I agree entirely: he’s a philosopher of the big-screen with as much to say to us as Jean Baudrillard, Pierre Lévy, Manuel Castells, or other of the thinkers of our present-day Technological Age. Cronenberg’s contribution to an interdiscilinary debate concerning genetics and eugenics, obsessions and fetishism, biotechnology and scientificism, is outstanding.

The “mood” in most of his films makes it clear that Cronenberg isn’t buying naively the ideology that says technological and scientifical progress will lead us to Paradise on Earth. It’s quite frequent, in Cronenberg’s films, that the attempt made by human scientists to reshape our bodies ends up messing things up badly. The transformations that the human body undergoes with its constant interactions with technology, the way our bodies and minds end up emboding technology, is one of Croneberg’s obssessions. The bio-ports in ExistenZ are the best example: holes in our bodys, similar to a computer’s entrance door, through which we can be plugged in to an artificial realm that cuts us off from day-to-day “natural” reality. But decades prior to that, he had already painted a gory portrait of the possible evolutions of television in his unforgetable Videodrome. There he explores the possible transformations of media, tripping on McLuhan’s ideas to end up creating a nightmarish dystopia, filled with hallucinationaty head-helmets and very weird mutations that give birth to a “new flesh”.

The effect of going through several roller-coaster rides in Cronenberg’s sci-fi park is, among other, this: skepticism about the marvels brought to us by advancements in technology and science. Cronenberg’s imagination may seem a little bit “paranoid”, in the sense that his fantasy springs from the fear that things can go horribly ashtray in human civilization while we venture into ever increasing degrees of artificiality. But there’s not a single drop of idealization of the past, or of Rousseau’s Natural Man, in Cronenberg’s work: he doesn’t seem to see any way backwards that will leads us to the way things used to be. It can be said that this cinema deeply anguised by time’s irreversibility and portraying the dangers of artificiality. It would also be unjust to say he’s condemning techno-cientific advancements; it seems to me Cronenberg’s tries to underline the ambiguity of this processes we have developed. They can have largely beneficial results for medicine and health, for example, but the other side of the coin – the nightmarish side – also deserves to be taken into account. An example: of course it would be silly to deny the importance of X-rays, for example, for the diagnosis of disease, but it would also be silly (and dangerous!) to ignore that a body that gets exposed to an excess of radiation can suffer terrible consequences.

Nothing guarantees us that the New Flesh is an evolution on the previous one – it may be a backward step. It may be the unleashing of forces we’ll be unable to control. It may be nightmares coming true.

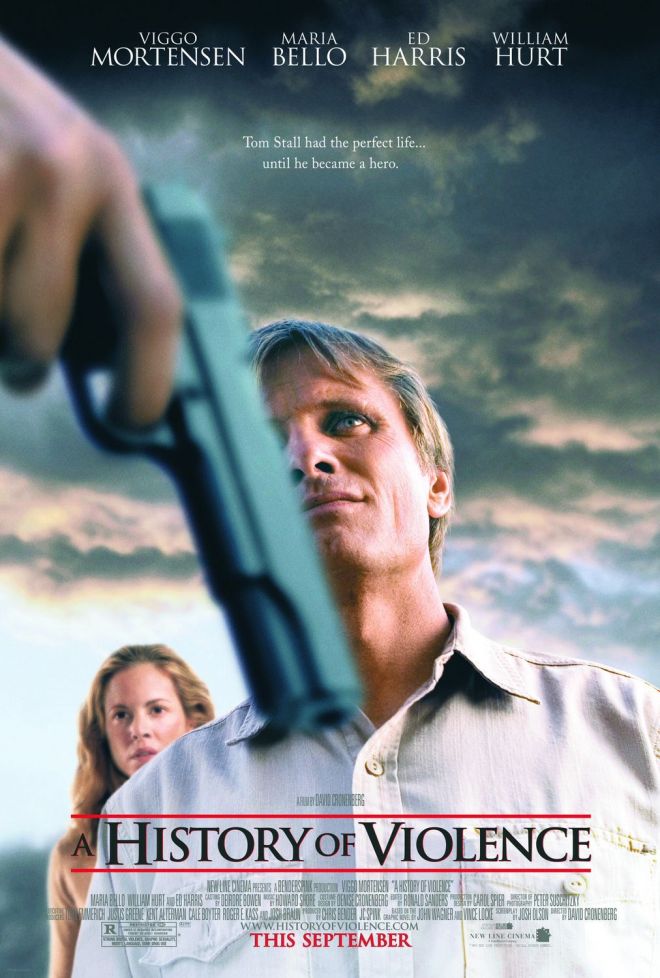

But it would be unfair to dismiss and undervalue Cronenberg’s artistic insight if we were to treat him as a pessimist always obsessed with disasters. Of course there’s lots of bloodshed in his films – just remember the ending of A History of Violence, that rivals with the most gruesome of scenes in Tarantino’s or Sergio Leone’s oeuvre. But a debate about violence in cinema can’t leave Cronenberg out of the picture: something quite original and unique is involved in this peculiar brand of cinematic ultra-violence. I would argue that the profoundness we can find in his films, if only we delve deep enough in their secrete layers, arises from an anxious questioning of the real ways of our world.

Cronenberg is deeply concerned by what’s going on with our world, even tough sometimes he seems to be filming some future or alternative society. Cronenberg’s vision has been labeled by many as “dystopic”, and I feel that’s quite accurate: this guy ain’t filming utopias where perfection and harmony have been realized. He’s much more into letting his worst nightmares get an objetified existence as film – so many others can dream Cronenberg’s nightmares. To sum things up, I would say that he engages in an anxiety-ridden cinema, with a dystopic flavour to it, with several irruptions of ultra-violence, throught which Cronenberg acts as a critic of Western commercial-industrial society. For this reason, among many other, he deserves recognition as an artist of many merits, among them the fact that he sounds the alarms on the possible consequences of mankind’s attempt to deeply re-shape Nature – including our own.

* * * * *

II. THE RE-SHAPING OF NATURE AND HUMAN ATTEMPTS AT SELF-TRANSCENDENCE

If there’s anything in our era that seems to be a shared truth, a point of conccord and no controversy, is that mankind’s been re-shaping Nature in massive scale and in various ways through technological interventions, medical innovations, advancements in genetic manipulation etc. If the artistic genre of “Science Fiction” is to survive as a culture force, relevant to the general audience, it needs to adress the dangers and anxieties that befall us all in such a world. That’s what Cronenberg’s cinema does so well. In the second part of this article, I’ll focus on the some of his films in which mutations are a central theme.

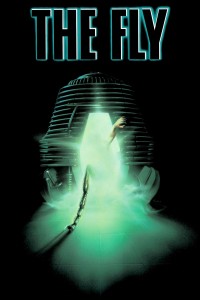

There are lots of Gregor Samsas in Cronenberg’s films: the process by which Kafka’s character gets transformed into a giant bug is not merely repeated in cinematic form, but serves as a theme upon which Cronenberg builds several variations. Seth Bundle (Jeff Goldblum), in The Fly, is the most obvious example: the scientist who gets things messed up in his laboratory and ends up getting his genes mixed with that of an insect.

There are lots of Gregor Samsas in Cronenberg’s films: the process by which Kafka’s character gets transformed into a giant bug is not merely repeated in cinematic form, but serves as a theme upon which Cronenberg builds several variations. Seth Bundle (Jeff Goldblum), in The Fly, is the most obvious example: the scientist who gets things messed up in his laboratory and ends up getting his genes mixed with that of an insect.

In Kafka’s masterpiece, the “mood” is of a horrific family drama that may remind the reader of Strindberg or Kleist. In Cronenberg’s case, we’re taken to a futuristic sci-fi scenario in which Bundle attempts to create a means of tele-transportation, which he deems likely to cause a whole revolution in the common limits of mankind. If he suceeds, history will rain down un-ending glory on him, and we’ll be honoured as one of the greatest scientists and innovators of all time – a new Galileo, a new Kepler, a new Einstein! But high hopes seldom live up to their promise in Cronenberg’s art.

There’s not a drop of cheap optimism in The Fly: it’s an enormously enjoyable film, well-crafted in all technical aspects, a masterpiece of narrative in cinema, but it’s message is far from being ear-candy. The Fly is actually a tragedy. For those of you who haven’t watched it, please jump to next paragraph so you won’t have your fun spoiled by my revealing of its ending. The Fly can be seen as a tragedy because it shows how a scientist goes through a terrible misfortune, having his organism monstruously transformed by the technological process he was aiming to master, and ends up having to ask the woman he loves (embodied by the gorgeous Geena Davis) to aid him in suicide. Life-conditions, for him, have been so screwed up by his experiment, that his only choice ends up to demand someone to put him off his misery. Josef K, in Kafka’s The Trial, feels he’s being killed “like a dog”; similarly, Seth Bundle’s demise is a terrible, gory and grotesque event – in which he’s murdered like a nasty fly. Things have turned out so horribly that the world needs to be rid of the monstruous human-insect he tragically became.

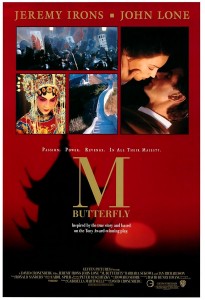

But it would be demeaning to say that Cronenberg is a mind that can only imagine transformations in the human body there are due to techno-cientifical intervention and manipulation. In M Butterfly, for example, the transformations that René Gallimard (Jeremy Irons) goes through have nothing to do with his genetic structure, or with surgery, eugenics or laboratorial side-effects. Gallimard, a french diplomat working in China at Beijing’s embassy, starts off his metamorphosis when he watches a performance of Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly. Cronenberg leads us, with his known talents as a compelling story-teller, in a downward spiral that shows how deeply Gallimard will have his identity changed and deranged in the life-process the film encapsulates.

But it would be demeaning to say that Cronenberg is a mind that can only imagine transformations in the human body there are due to techno-cientifical intervention and manipulation. In M Butterfly, for example, the transformations that René Gallimard (Jeremy Irons) goes through have nothing to do with his genetic structure, or with surgery, eugenics or laboratorial side-effects. Gallimard, a french diplomat working in China at Beijing’s embassy, starts off his metamorphosis when he watches a performance of Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly. Cronenberg leads us, with his known talents as a compelling story-teller, in a downward spiral that shows how deeply Gallimard will have his identity changed and deranged in the life-process the film encapsulates.

At first, Gallimard is shown as an arrogant person, very ethnocentric, certain that he’s the living embodiment of civilization and finesse: he believes that Western presence in China and Indochina is cherished by the majority of the population, and he’s certain that the United States is going to suceed in the war efforts in Vietnam and Camboja. He’s a married man, and his wife (Barbara Sukowa, who recently embodied Hannah Arendt in Margareth Von Trotta’s film) would never suspect Monsieur Gallimard of being anything but a loving, faithful husband – and definetely heterossexual.

M Butterfly, among Cronenberg’s films, is one of the richest in terms of the possibility of discussion of gender matters. Sexual identity is shown as something that’s far from solid and immutable – it also undergoes changings and mutations. Gallimard thinks he’s straight, a “normal” heterossexual guy, but his experience in Beijing’s opera will call that into question when he falls in love with an opera diva (a man dressed as a woman). Gallimard ignorance of Chinese cultural reality is made obvious by the fact that he seems to be completely unaware that female characters, in China’s operatic spectacles, are played by men – a custom that has existed also in the past of West (for example in England, during Shakespeare’s epoch, something described, for example, by Richard Eyre’s brilliant film Stage Beauty).

M Butterfly is filled with Gallimard’s delusions: his beliefs doesn’t correspond to the facts. He, for example, believes he has fallen in love with a chinese woman, an opera diva, when in fact he’s been used by a Communist Party spy who’s gathering information about Western military actions in Indochina. Gallimard believes he has found true love outside the bonds of marriage, and abandons himself to the calculated seduction of the transvestite-spy. When he wakes up to what’s really going on, the whole structure of his personality will be shattered.

In Puccini’s opera, the Jananese girl kills herself after being abandoned by the american foreign; in Cronenberg’s film, the positions shift: now the Western guy is the one who’s going to kill himself because of the abandonenment he suffered. When the dream cracks and dies, when Gallimard finds out all the truth and realizes he has been used, then love’s past utopia metamorphosis into suicidal frustration and self-destruction.

The Fly, I claimed such paragraphs ago, could be seen as a tragedy; well, M. Butterfly is another. Its tragic core lies in the crack in identity’s continuity. Gallimard’s psyche gets cracked by the sudden death of his illusion. He was severely mistaken about China – and never really knew the “woman” he claimed to love. In the end of the process that the film narrates, he’s utterly confused about his own sexuality, uncertain and shaken: he lost all the prior confidence in his “straitght-ness”, his “masculine normality”. In his death trip, in the ritual in which he sacrifices himself, very Orientaly, as if attempting a hara-kiri, Gallimard has become himself the Oriental and the Transvestite.

The well-defined limits of his previous personality gets crushed by new experiences. He’s boundless and insane. He cuts his own throath in front of the audience of prisoners, as thus becomes an embodiment of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. The brilliance of this masterpice in filmmaking, which I consider one of the most under-valued classics of the 1990s, lies in authentic description of the mutations that can occur to the human body and mind.

Gallimard, in M Butterfly, lived through a severe “personality crisis”. Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), in A History of Violence, will struggle with something similar. In this film, Cronenberg focuses in his attention on an attempt at vountary change of identity. The man we get acquainted with at the beggining of the film, Tom Stall, we’ll soon discover to be a fabrication of Joey Cusack, who wanted to shed his skin like a serpent and abandon his own past behind.

Tom Stall is an idealization of the real flesh-and-bones man, Joey Cusack, who, after too much bloodshed in gangster environment during his life in his native Philadelphia, decides he’s gonna leave a life of crime behind and become a model citizen and family-man. When Cronenberg’s film starts, it seems he has suceeded: he has a beautiful wife, and they engage in very sexy affective playfulness; their two kids seem to be doing quite allright, despite the bullies at scholl and some baseball fights. But when something is going allright in a Cronenberg film, prepare yourself: it’s a clear sign that we’re headed for disaster.

Joey Cusack tried to transform his identity, tried to impersonate his fabrication of an ideal personality, but forgot something: everyone who knew in his past would lot easily permit his sliping away unto other identities. There’s a phrase in P. T. Anderson’s Magnolia that seems to be a description of his situation that fits like a hand in a glove: “We might be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us.”

Ed Harris’ character, in the film, seems like a scary monster that sticks his head out of the abyss of the Past. Joey Cusack may have felt he had enough of his past, but well… his past hadn’t had enough of him. He’s bound to experience a dark re-awakening of the past who he mistakingly supposed he had buried. A History of Violence, despite being a very exciting thriller to watch, reveals a lot about the human condition. A man wants to throw away who he was and re-shape himself, becoming someone else: who among us haven’t felt a similar desire at some point in our lives? But the past is embodied in ourselves in such ways that we’ll never be able to discard it like a serpent does with its skin.

To sum things up, I would argue that Cronenberg’s artistic merit lies in his ability to portray and discuss humanity as a dynamic entity, changing through time, and not merely an instrument of outside forces (like a leaf in a river stream), but also in attempts at self-reshaping and self-transcendence. Throughout the history of Western philosophy in the last three millenia, some great thinkers have stressed the mutability of Nature: Heraclitus, for example, said that “everything flows” and that it’s impossible to bathe two times in the same river; his 19th century disciple, Friedrich Nietzsche, would also suggest in his visionary philosophical poem Zarathustra, the changeability of Man, depicted as a tight-rope walker that traverses the abyss whose margins are the beasts (behind us) and the Übbermensch (ahead us).

The impression I get after having travelled along with Cronenberg’s creations is that he deserves to be seem as a philosopher of cinema who’s deeply concerned in understanding mutations. Humans, for Cronenberg, never were and never will be fixed creatures: we’ll wander through Earth sheding our skin like serpents and trying to transcend out present through re-shapings both of our natural environments and our bodies and minds. In Cronenberg’s oeuvre, we get acquainted with the idea of Humanity as a mutant entity whose future glory is far from guaranteed: it may happen, his films seem to say, that History turns out to be a nightmare from which we won’t be able to awake. And simply because of this: the nightmare is real, and we ourselves are monsters of our own creation.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Here’s a selection of Cronenberg’s greatest works:

- Stereo (1969)

- Shivers (1975)

- Rabid (1977)

- The Brood (1979)

- Scanners (1981)

- Videodrome (1982)

- The Dead Zone (1983)

- The Fly (1986)

- Dead Ringers (1988)

- Naked Lunch (1991)

- M Butterfly (1993)

- Crash (1996)

- eXistenZ (1999)

- Spider (2002)

- A History of Violence (2005)

- Eastern Promises (2007)

- A Dangerous Method (2011)

- Cosmopolis (2012)

[youtube id=http://youtu.be/jD3vnPh12Kw]

Publicado em: 30/01/14

De autoria: casadevidro247

comentários